I am most grateful to Rosemaria Regy Mathew and S. Balasundari for inviting me to introduce this book. The book presents a field of facts, statistics, opinions, and affects and the implied reader can move within its activity to practice a multisituated (Kaushik Sunder Rajan) point of view. This book is focused mainly on Kerala. Books from other parts of India of the same sort could enrich the movement to re-imagine menstruation.

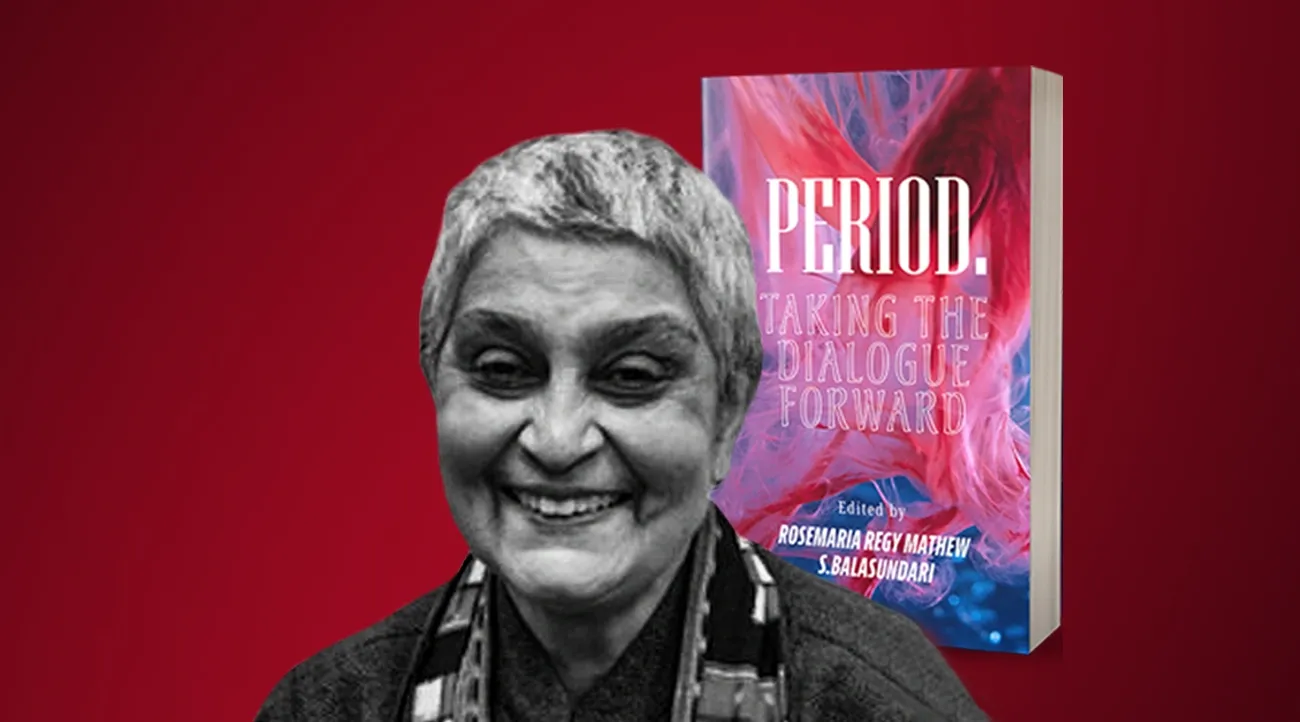

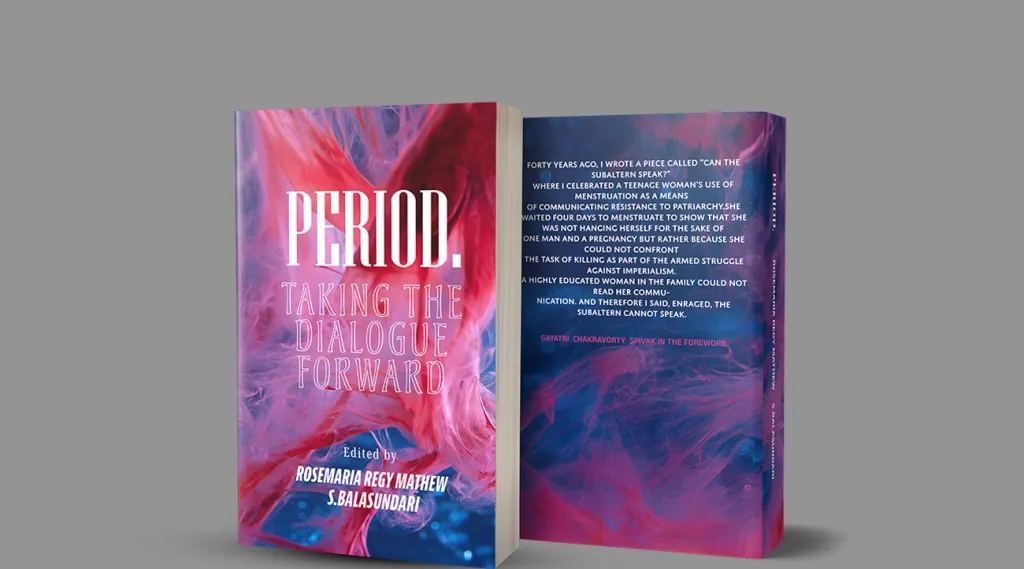

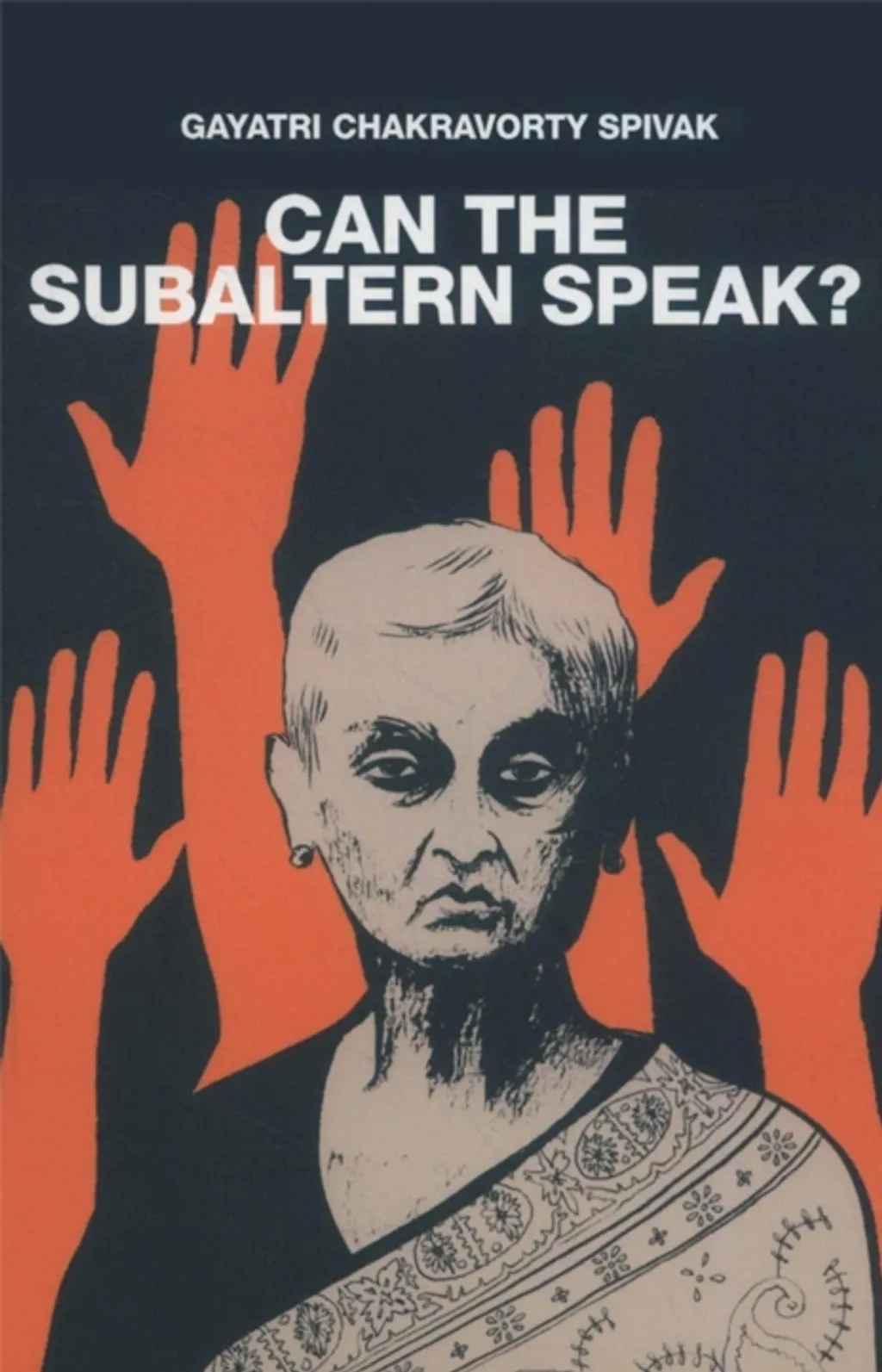

Forty years ago, I wrote a piece called “Can the Subaltern Speak?” where I celebrated a teenage woman’s use of menstruation as a means of communicating resistance to patriarchy. She waited four days to menstruate to show that she was not hanging herself for the sake of one man and a pregnancy but rather because she could not confront the task of killing as part of the armed struggle against imperialism. A highly educated woman in the family could not read her communication. And therefore I said, enraged, the subaltern cannot speak.

In these last forty years, I have had thousands of reactions to this piece, but no one has noticed that the central argument of the essay is that a woman used menstruation as a means of communicating resistance and was not heard. I therefore think that the task of rearranging the desire to perceive the usefulness of menstruation and not simply to romanticize it, is much harder than we might think. In the longest piece in the collection, by a Western woman, there is a sense of this particular problem. As I havealready stated, this is a multisituated book, and the reader will be able to engage with her own point of view, pro or contra, among the writers.

The real task for all of us now is to achieve the mindset which will acknowledge that the planet is in disaster. Within this context, the most important figure for me in the book is “Komal, whopractices open bleeding, [and] is forced to sit in a corner of her house during her ‘time’ due to lack of access to absorbent cloth, water and sanitation” (98). To have “open bleeding” as the normal practice of menstruation and to have that be impossible in its normality because of the slow disappearance of the enhancement of a tiny bit of the Anthropocene – the regular enhancement of salt-pan exploitation – the slow drying up of water (as in Namib ia) — teaches me a lesson about solidarity within the menstruation movement. Open bleeding is a choice that I cannot imagine. Un like the activists who write in this book, my work is slow. I know that I have made some villagers in West Bengal want to use toilets by my insistence on always getting one from the Government wherever there is a school inspector’s room in a schoolhouse forme to stay. When this happens, I humanize the toilets, sometimes even use them to make the family feel at home. But how can I do this when the practice of bleeding freely, for financial reasons ornot, is beyond my own imagining for my own body? And what a tremendous and sustained undertaking of “development” there would have to be, even going beyond the fact that the state seems to be legally protected against helping them “develop” – making the children want to learn, but why, how? These last two questions I have spent the last thirty five years of my life asking and answering repeatedly, making mistakes, learning, trying to get into their interiority, for otherwise there can be no lasting change. In your book, there is a certain romanticization of menstruation as a wonderful natural thing.

Can this bleeding freely “practice” be idealized? Another group of essays in the book gives details of makingpads available to women (if you want to criticize commodity marketing around this, you will find such a piece in this multisituated book.) How will you generate a desire for pads in this group of women and how to support it? As of now, what we hear them say is that they try to direct the bleeding to the same spot on the ghaghra, so they don’t have to use too much water to wash the stainout; for the competition is to use the water for cooking for the famly. The Bagariya women of Ajmer remain for me a limit as I read.

My work, focused in one area for many years, is not concentrated on menstruation but on the general rearrangement of desire for social justice for all. It must refrain either from anthropologizing or from collection of statistics. (In fact, one of the incidentalconsequences of my work is the exposure of the corruption in the creation of statistics for grabbing resources through inching up indexes.). These women may be poor but they are not stupid. They fully understand that that kind of work comes from another class and produces some top-down good from time to time. I have spentdecades in order to separate myself from that class in order to do my work. I realize I must now make straightforward enquiries about the menstrual textuality of the five villages where I hang out.

Checking it out on the subaltern level, not in a statistical/anthropological (fieldworking) way – my general advice, we find that any celebration of a religion as providing succour for imagining menstruation as positive – be it Catholicism or Tantra or Kamrup Kamakhya – would be to refrain from just citing mostly Western texts and actually move in with folks to see if in actual practice the wonderful religious claims are fulfilled. I would recommend my own attempt at this in “Moving Devi,” looking at the do-it-your self tantra books distributed at subaltern village fairs. Also, be focused on trying to enter the space of subaltern women before you simply thrust upon them (196f) how to re-think menstruation. Do not ask that rural women make up new words to think about menstruation in a different way. The real task, I say after spending 35 years with rural women and men, is to try to enter their space to see why they would begin to want to be like activist metropolitan white folks wanting to romanticize menstruation as a sign of opposition, rather than remain within whatever discourse it is that they use for talking about it. Could it be that some of them feel, as Ruth Vanita and I do, that menstruation is a nuisance, even as we strongly oppose patriarchal ideologization of menstruation as a shame that makes women inferior and dirty?

Therefore, and once again, do not present a certain class of women from a certain area as “India,” but, being careful about giving caste-, class-, and region-designations, please continue the work. Short-term: by all means pads and underwear drives shouldlead. Long-term: think of the difficult ways of doing sustained work with disenfranchised women and men to imagine their interiority, to see how it is possible for them to want to change this millennial structure of gendering rather than inherit a fight from self-selected moral entrepreneurs from the middle class. Use the heterogeneity of this book for free practice rather than simply assigning it for classroom teaching, although that too would be good to generate some revenue.

In this introduction I am placing myself within the debate rather than writing remotely, because this multisituated book invites such a move. I would therefore say that before the glorification of menstruation as the inauguration of motherhood, it is important for me, in the interest of full disclosure, to say that, as a result of training by an extraordinary mother, I am aware that “maternalism” – matrivada – and “teacherism” – guruvada – have been destructive forces in our country and elsewhere. Again, I adore my mother’s extraordinary genius – this has nothing to do with loving your mother. My icon here is Saradamani Chattophadhyay otherwise known as Sri Sri Ma or Sarada Devi. She was my father’s guru – an illiterate woman of extraordinary brilliance and insight, who preached the ethical by deconstructing the maternal, ratherthan rejecting it. I have described it at the end of “Moving Devi,” in Chintar Durdasha, as well as my as yet unpublished lecture “Imagination, not Culture,” given at the Harvard Divinity School in 2008. How did she menstruate? Having chosen celibacy, in agreement with her ecstatic husband, how did she write it into her life?

If I am placing myself within the debate, I should share my own background with you so that you can situate what I’m saying here. Please remember that I have just insisted that we must use class caste-designations. On page 173 of this book I encounter the sentence: “Among Bengalis, it is believed that menstrual blood has potent energizing properties.” I am a Bengali, but I don’t believe I would be an example of the “Bengali” that is being described here.

I was born in1942. Both my parents were highly educated. Both fought against compromising circumstances. My father because of rural origins and an intense “not rich” class awareness. My mother because she was married at 14 and had my brother at 15. By the time I came along, they were plain-living, high-thinking, secular nationalist intellectuals devoted to their children. My father was a doctor. My menarche continued through two cycles. I was 11. He explained to me I should go out and run if I had cramps. He added something which was most interesting: we men- said he only feel one message from the body, when the stomach twists and we feel hunger. You women can feel two: hunger and, when the uterus twists, you feel cramps.

I realize now what my father was saying that menstruation gave us more. And that this has been incredibly important for me all my life. He said it as a bit of gentle fun. I have no idea if what he was saying was correct or if he was just saying it to an 11-year-old child. But it made a great impact. This is why I can understand why Christopher Knight of London University would say that perhaps at first women wanted to keep all of this to themselves and then, through the usual gendering, it was taken away by men (136). As for my mother, she told me this: when you are told – she said that you should not enter the shrine room or the temple because you are menstruating, walk right ahead, go in and tell whoever told you this that your mother told you to enter and they should speak to me. So I was cool.

I want now to share with you something that I was able to write just before I read your book. I was looking at the translation of an interview I had given some years ago, which did not carry the point I was making because the translator had missed the point aboutmenstruation. When you say that Indian women have certain images restrictions etc. again you forget class. The woman who was translating my interview, English-oriented upper classs, did not know that the phrase I was discussing came from the Mahabharata and describes Draupadi as she walks into the Council chamber in her menstrual clothes bloodied. This is what I wrote: “Nath- abati Anathabat – lorded as if lordless. That Draupadi menstruating is in her female being – although she had husbands – when she’s (form of appearance the phenomenologists would say), menstruating –it is as if there is no husband, because during that time she is not childed/pregnant. This is the meaning of lorded yet as if lordless. The lording – patriarchal hold on the female body – is, temporarily at least, at bay. So, being in your stridharma – menstruating -- means that for this period of time the man has been defeated. This relates to the feeling of they – the women - have more; which underlies all the effort at re-writing menstruation as a mark of shame. Remember the sense of shame can also be an enjoyable affect, I wish I could write more about this –you usually have to learn how to teach yourself that people are very unlike.

For protection we used cloth to make homemade pads. And that seemed the most comfortable. These were made with clean bedsheets, saris, dhotis, etc. which were old and ready to be torn. I did not change to pads until I went to the United States in 1961 at the age of 19. I did not like pads. Cloth was good. Disposal of these homemade pads was incredibly complicated, I now have forgotten how we daily solved that problem. After the age of 15 when I entered the boys’ college and so graduated to saris, I didnot wear underwear. I am of course completely for underwear and keeping yourself dry etc. but I must say, I was also completely comfortable not wearing underwear. The sari has a long end that you can use to cover your backside, so stains were not a problem. And having these problems created a kind of comradeship among female friends.

Before I leave you I would like to introduce Jamini Karmakar who taught me, in the Jharkhand-West Bengal rural area where I do my focused work, how to urinate in public using the sari like a tent, so that no one knows you are urinating and you do not wet yourself.

She knows that because she taught me the skill more than thirty years ago, which is invaluable in the rural areas, I do show her picture to people. You see a door behind her. I have slept in that room a number of times. The fact of deciding on no underwear is incredibly convenient.

In Komal and her cohorts I had found a limit to my focused work of epistemological performance supporting material change. I want to end by naming a general limit: the Rohingya women who are obliged to live in the water-logged muddy encampments in Southwestern Bangladesh. I am a Citizen Ambassador for the Free Rohingya Coalition. So I am certainly in touch with global activists surrounding the Rohingya genocide where rape and sexual l violence are a weapon. But I cannot imagine living under the circumstances of statelessness in which the encamped Rohingya women survive. Everything I have written finds in those muddy waters their end.