Jafar Panahi, an internationally acclaimed filmmaker known for his commitment to justice for his traumatized characters, presents a compelling vision in It Was Just an Accident. The film serves as an impassioned plea for justice, resonating with emotional intensity. Although the narrative escalates into rage, the film occasionally adopts a comic thriller tone, subtly critiquing authoritarian rule. Panahi employs this approach in other works addressing oppression in his country, such as Taxi, Closed Curtain, and No Bears. Even the film's moments of humor carry significant moral weight.

The narrative is initiated by a seemingly minor accident, where the husband, Eghbal (Ebrahim Azizi), driving at night with his pregnant wife (Afssaneh Najmabadi) and daughter (Delmaz Najafi), accidentally hits and kills a dog. This misfortune sets in motion a chain of unforeseen, escalating consequences, but the moral machinery begins turning even before the car stalls.

Eghbal escapes accountability for killing a dog by claiming it was an accident. In contrast, Vahid and his team devote considerable effort to determining whether he is the torturer, underscoring their commitment to avoiding the execution of an innocent individual under the pretext of an accident.

Here, in the dark, the wife offers the opening defense that will echo and be refuted throughout the entire film: “It was just an accident,” she says, adding that “if god put it on our way, it must be for some reason.” This single moment—the dog's life snuffed out and then instantly rationalized—acts as a moral precedent, an original sin of evasion. By labeling the death "just an accident" and attributing it to divine will or flawed infrastructure, the wife attempts to cleanse the act of personal responsibility. It’s the language of a society accustomed to suffering and quick to minimize accountability. This acceptance of a life’s destruction, treated as a trivial inconvenience, foreshadows the widespread, normalized inhumanity that state violence relies upon. A life is taken, and the consequences are dismissed as "just the way things are." Much like the creatures whose lives are destroyed on this street, by virtue of this misfortune, their lives will be diverted.

What begins as a minor accident sets in motion a series of escalating consequences. The car stalls out. A passing motorcyclist offers help if they follow him to his warehouse workplace. That’s when Vahid (Valid Mobasseri), the man’s boss, spots Eghbal and hears the squeak of his artificial leg. The next sound is all unholy hell breaking loose.

Vahid thinks that Eghbal is “Peg-Leg,” an interrogator at an Iranian prison where Vahid was tortured. Though prisoners were blindfolded, Vahid tells Peg-Leg, “I’d know the squeak of your artificial leg anywhere.” Vahid says this after he has kidnapped Peg-Leg and taken him out into the desert to bury him alive. Talk about escalating tensions. Eghbal insists he is not Peg-Leg since his limb was amputated only last year and he has the fresh scars to prove it. This introduces the film's ethical core: the profound doubt that troubles Vahid and drives the subsequent road trip.

It is this profound casualness toward harm in the opening that the film's central plot directly inverts and confronts. The stakes are magnified from a dog's life to a human's life. Yet Panahi demands that the audience note the stark difference: Vahid and the former prisoners refuse to let the deed be excused as a mere accident. Unlike the wife who casually dismissed the canine’s fate, Vahid’s team struggles with an immense ethical burden, spending crucial time and emotional energy seeking confirmation because they do not dare kill an innocent man by saying it was “just an accident.”

The word "just" in the title functions as a brilliant linguistic and philosophical knot, holding three distinct and conflicting meanings in tension that define the film’s moral landscape:

"Merely/Only" (It was just an accident.): The language of evasion, used to minimize consequences and avoid guilt—the oppressive comfort offered by the system itself.

"Righteous/Fair" (The pursuit of justice.): The decisive goal fueling Vahid’s vigilante act, the desire for moral balance against the crimes committed.

"Exact/Proper" (Is he just the right man?): The terrifying ethical threshold. They must be sure he is the just (exact) man to satisfy their demand for justice. To kill the wrong person would erase their moral claim and turn them into the very thing they despise.

The tyranny of "just" (merely) is Panahi's central target. The journey itself is a refusal to let their trauma, or the possibility of future violence, be dismissed as "just an accident."

The film finds its philosophical counterpoint in the work of Hannah Arendt, who observed the trial of Adolf Eichmann and coined the phrase, the banality of evil." Panahi uses the uncertainty of Eghbal’s identity to show that the system’s cruelest power is reducing unimaginable horror to routine and the torturer to a man with a squeaking leg. Yet, where Eichmann represented the absence of thought, Vahid and his companions embody the excruciating presence of ethical consideration. Arendt posited that this "consideration"—the act of imaginatively visiting the place of the other—is essential for moral judgment. By demanding proof, by gathering witnesses, and by debating the fate of their captive, Vahid’s desperate committee forces themselves into a profound act of collective thought. They refuse the easy, thoughtless release of vengeance. They are trying to restore the very capacity for judgment that the totalitarian state had sought to erase.

Vahid needs more evidence, so he sets out in his white van to find others tortured in the same prison. Panahi masterfully turns what could be a grim descent into vengeance into a strange, deeply human group project, operating under the guise of a road movie.

Vahid assembles a ragtag crew of fellow former detainees, each with their own way of sensing and identifying "Peg-Leg." One works in a bookstore and urges mercy; another says to kill him anyway. Yet another former detainee, Shiva (Maryam Afshari, performing without a hijab), is a wedding photographer who brings along the bride (Hadis Pakbaten), who is eager to confront the man who raped and tortured her. The bride, Golrokh, is wearing her satiny white gown, and she, too, is an ex-prisoner.

Vahid identifies him by sound, Shiva identifies him by smell, and Hamid identifies him by touching the scars on the man’s leg. The invocation of the sensorial intimates that these people are being governed as much by instinct and emotion as by logic, inspiring snap reactions fueled by anger.

The film's strength resides in its genuine ensemble cast, uniting a vibrant collection of individuals bound by mutual trauma and a fervent desire for retribution. Far from diminishing the gravity of their mission, the inherent humor sharpens the stakes. Panahi invites the audience to share in the laughter of these characters, thereby intensifying the emotional weight of their collective ordeal. The journey is marked by a series of absurd yet vital incidents: the van breaking down, a sudden birth, the exchange of bribes, and lively disputes culminating in illuminating, witty reveals. Beyond the clever dialogue, editor Amir Etminan's masterful use of pan shots contributes equally to the silliness and the unexpected comic rhythm.

Panahi isn’t really after a whodunit. Whether this man is truly their oppressor matters less than the emotions he stirs up—the way trauma lingers, how memory becomes both a prison and a weapon, how survival doesn’t always mean freedom. The film is littered with prisons, literal and metaphorical.

Panahi’s film shares its retribution theme with Death and the Maiden, the play and film written by Ariel Dorfman that evoked the tortures inflicted in Chile by the dictator Augusto Pinochet. But the agonizing mystery of identity and the cyclical nature of violence more closely echo Wajdi Mouawad's shattering play, Scorched (Incendies). The grotesque depravities recounted by Panahi’s characters, particularly the rape and torture suffered by Golrokh, find a haunting parallel in the systematic torture and sexual violence inflicted upon Nawal Marwan, the mother in Mouawad’s work, by the very regime she sought to defy. Panafileaves the ending of his film ambiguous. But is it really?

We learn that Vahid has a core of decency that gives pause about carrying out the actions he’s undertaken. He displaces this ethical uncertainty onto a question of verifying the judge’s identity. Like Vladimir and Estragon in Beckett's Waiting for Godot, the characters in It Was Just an Accident spend a lot of time waiting. Even after Vahid and the others return to the open grave, they remain uncertain about the prisoner’s identity and equally unsure about what to do. From here, the enduring symbol of the absurdists' setting is transposed onto the Iranian desert, marked by the solitary standing tree that provides the only shade and silent witness to their ethical debate. The journey becomes literal and philosophical, filled with stops and starts, digressions and circularity, as they endlessly debate next moves. They know that they may well be digging their own graves, too. The film’s direct reference, with one character noting, “From afar, you reminded me of that play we saw,” seals the link to the Theatre of the Absurd. Their existential agony is not solitary, for Panahi very clearly wants you to know that, like Estragon and Vladimir, they’re not waiting alone.

The road trip of revenge is interrupted when the risk of collateral damage becomes palpable. Vahid and his fellow travelers find themselves ethically compromised by this unexpected complication, which suddenly casts them as perpetrators of harm against the innocent and not simply avengers of their own victimization. They are trying to restore justice (righteousness) to a world where their suffering was consistently reduced to "just" (merely) a casualty of the system. The film’s descent into hell, where the line between victim and perpetrator thins, mirrors the devastating moral contradiction at the conclusion of Scorched.

In Mouawad’s ultimate, tragic resolution, the twins, Janine and Simon, uncover the unbearable truth that the "father" and "brother" mentioned in their mother Nawal's will are the same person: Nihad, her long-lost son who grew up to become her rapist and torturer. This ultimate chaos is felt in Panahi’s work through sensory recognition, where the survivors seek the truth not in documents but in the body, much as the twins in Mouawad’s play eventually see their devastating truth in their father's eyes, a moment of irrevocable recognition. Crucially, this sensory identification is the only path forward because, like Panahi’s tortured prisoners, Nawal was blindfolded by her captors and could only identify her future rapist and torturer through the faint, unreliable remnants of her memory: his distinctive voice and the memory of a clown nose.

While Panahi leaves his conclusion chillingly ambiguous, Mouawad offers a path toward potential healing through confrontation. In Scorched's final scene, the twins deliver Nawal's two letters to Nihad—one filled with contempt for the torturer/father, and one filled with love for the firstborn son/brother. This double message forces Nihad into profound silence, and for Janine and Simon, it breaks the generational cycle of rage. Both Panahi and Mouawad, profoundly humanist artists, insist that knowledge and confrontation are the only routes forward. Where Panahi asks, "What kind of people do we become after surviving the worst?", Mouawad answers with the twins sitting together, "listening to their mother's silence," suggesting that absorbed truth and potential forgiveness can triumph over despair.

This all sounds heavier than it plays. Panahi keeps things relatively light, with just enough incident to fill out a brisk hundred minutes of screen time depicting, primarily, the events of a single day.

One of the film’s best triumphs is the way it gives humanity to people who are often reduced to statistics, footnotes, or abstractions—the victims of state violence and war crimes. Panahi doesn’t frame them as symbols or martyrs but as living, breathing people. To watch them is to be reminded that survival is not just a matter of enduring violence but of refusing to be made invisible.

Panahi’s films deeply explore societal issues in Iran, including the struggles of minority groups. The main protagonist of the film is an Azeri Iranian, the most significant ethnic minority in Iran. And speaking of this bottled-up rage, we can talk of Shiva. Mariam Afshari (Shiva) was an assistant director and worked in production, with no prior acting experience! The name “Shiva” is also derived from the Hindu god, who has both benign and fearsome aspects, and is known as the “Transformer”. With the car's red lights illuminating them in the dark, it looked like they were in hell. A really striking image. This red light we also see on Eghbal's (Ebrahim Azizi) face at the very start of the film. Panahi provides enough cues from the beginning to indicate whether he is the torturer.

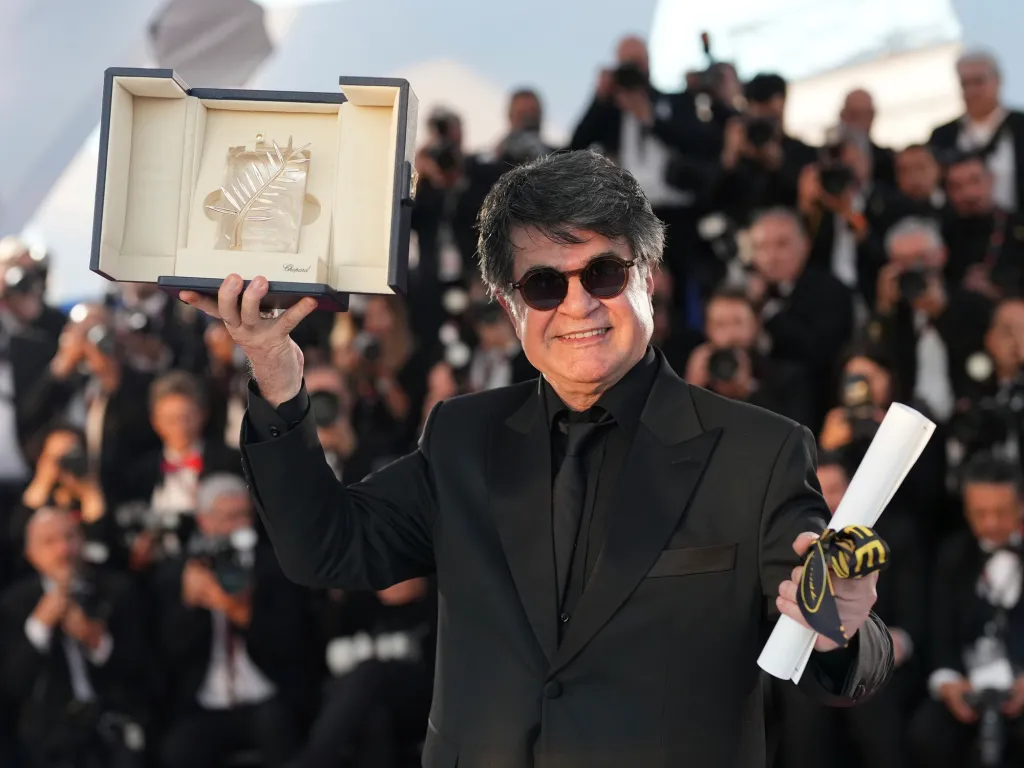

Despite the shadow of trauma, Panahi’s films are never bleak, but burst with life, humor, and curiosity. It Was Just an Accident defies easy classification, merging genres into a powerful tragicomedy and ethical thriller. This could be his most political work so far. The last 20 mins are phenomenal, intellectually and emotionally. The film is a direct cry from the heart, borne from the director’s own experiences and debt to fellow political prisoners. Panahi’s long history of persecution, including his 2010 conviction and 20-year filmmaking ban, affirms his uncompromising integrity. The narrative slowly builds to a masterful, inevitable descent, confronting the audience with pure dread. The director refuses to simplify his characters, questioning the moral calculus of survival instead after enduring the worst. His final statement lies in the ambiguity of the line separating personal harm from systemic injustice. Made covertly and without state permission, the film’s ultimate reward was the Palme d’Or at Cannes, a testament to his art and resilience.