It was raining in Delhi yesterday evening and the chill was entering Vivan's home where his body is kept. I could see his friends, former colleagues, and beloved comrades walking in and paying their last respects to the man whose name is synonymous with Indian art (Today by noon his body will be cremated at Lodhi crematorium). Indian art without him is an idea we will all get used to only slowly.

Last Sunday, I visited Vivan at the hospital. As I walked into the room, Geeta told me that Vivan is leaving us.

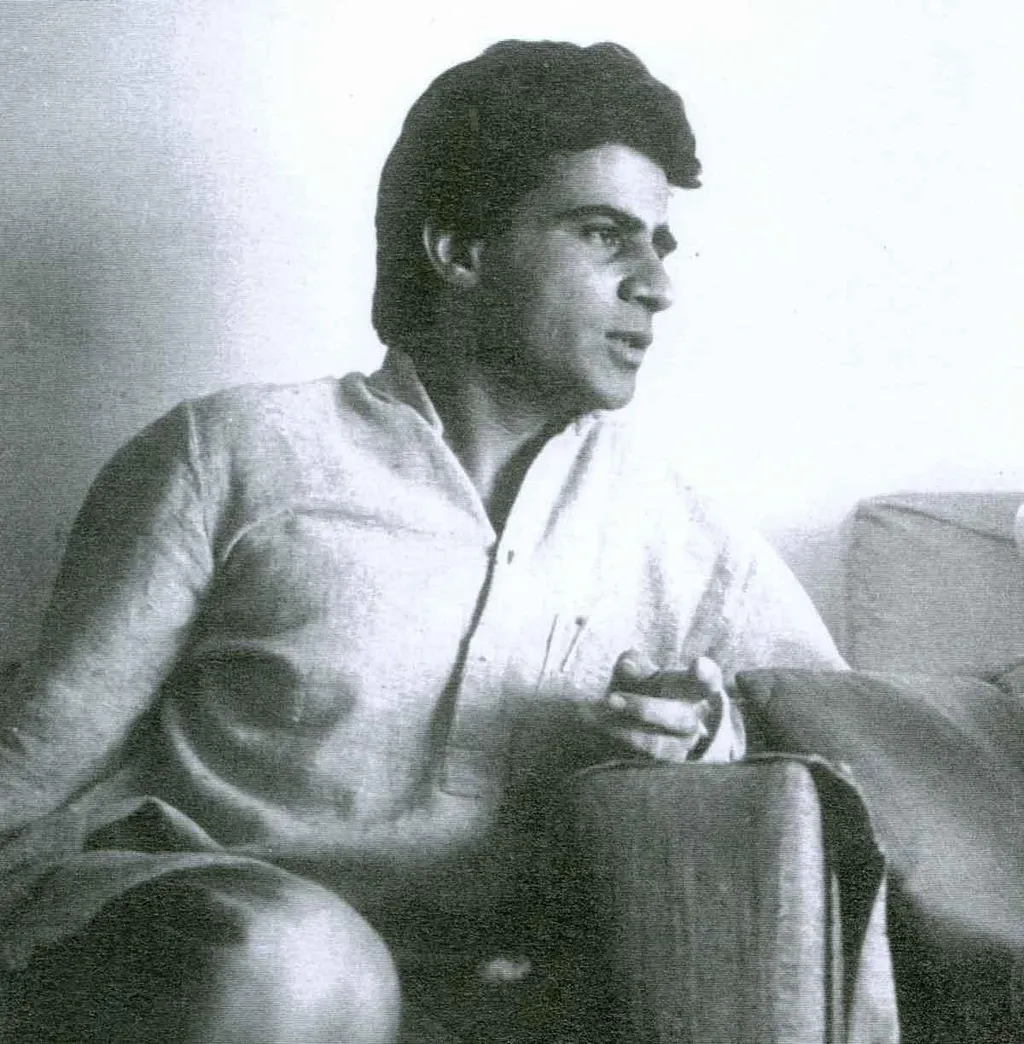

I sat for a while with Geeta inside the ICU where she recalled the long-term camaraderie they shared as partners. She also dwelled on the dreams of their youth, tales of courage and energy. She said she felt blessed to have shared her life with him, one of our most talented artists who was educated both in India and abroad, who was born into privilege and yet rebelled against the system all through his life and taught many others to fight on against injustices and be heard. He also inspired thousands of artists to be passionate about what they were doing and to intervene in social causes in their ways.

After meeting Geeta at the hospital, I decided on a whim to take a walk to the Raj Ghat, and through the crowded Veer Bhumi and Shakti Sthal. At Shanti Vana, Nehru's Samadhi, there were no signs of any visitors. It was empty and I found the experience rather unsettling. There was a reason, because here I was on these grounds, reminiscing the life of a liberal, a deeply political, and a secular artist and a comrade I had the opportunity to know and I cherished it and I was proud of knowing him.

Losing a social activist and an active member of the Indian political art scene brings a void, especially in times as uncertain as this one that we are passing through.

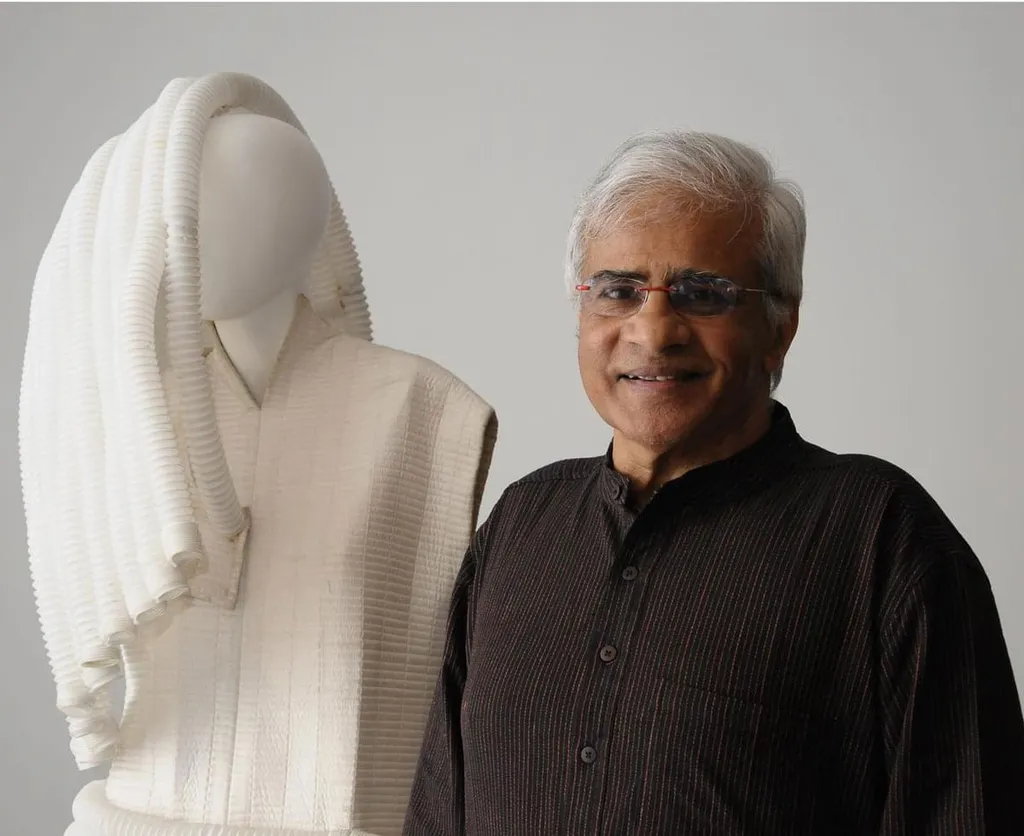

Today, we are all either sitting or standing around sharing the grief of losing him and the passion with which he lived life! This year he was at work tirelessly, he was involved with many projects, including the Sharjah Biennale, and his works are also shown at the 2022 edition of the Kochi Muziris Biennale. He was also planning an extensive international museum project. Now, as I look back at his life, I have to say that he lived his life without capitulating on the values he held close to his heart. He was an unwavering man with a futuristic vision for art education and practice.

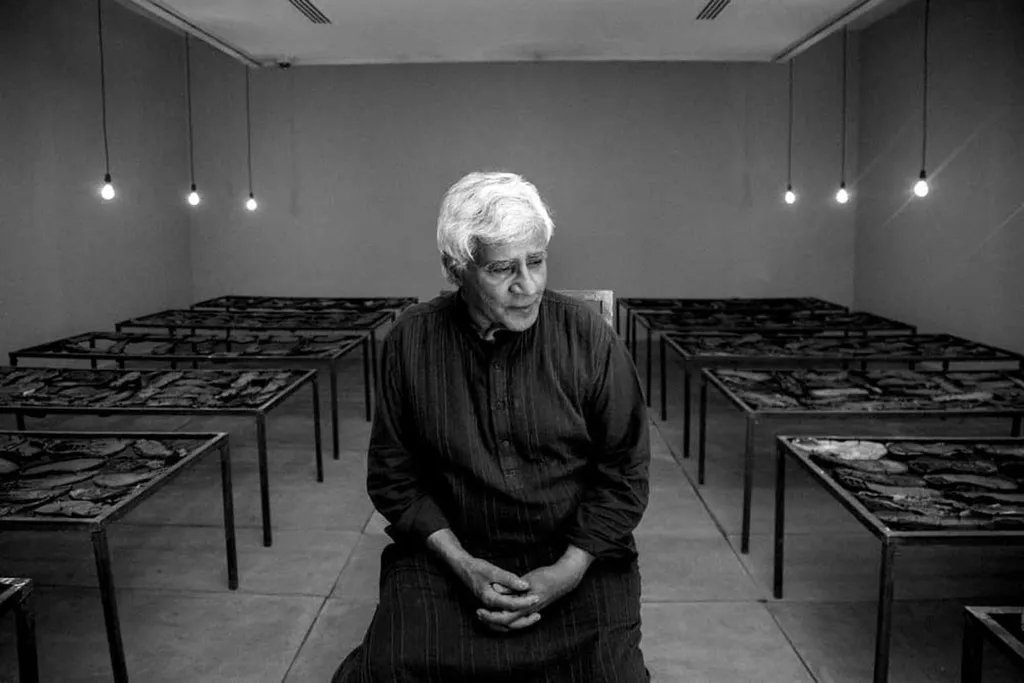

I first heard about Vivan after I moved to Bombay to learn textile design in 1992 at Sir JJ School of Art. As an artist who was vocal about responding to the crisis around him, Vivan was part of various art resistance movements that happened following the demolition of the Babri Masjid and the riots that shook Bombay in 1993, and his art reflected dissent, weaving together what is personal and political. Post-Mumbai riots, Vivan made an installation titled 'Memorial' which comprised objects and structures which carried the marks of the brutalities of the riots and blasts using photographs pierced with nails, and metal trunks among others. He brought to the fore the pain of mindless violence on the streets of India's commercial capital. Meanwhile, it is important to note that Vivan was one of the first contemporary artists in India to explore installation art. Post 92 Indian art became a site of multimedia expressions and Vivan was a pioneering presence with strong political rigour. My moving towards art - mainly installation art and activism - was also influenced by such events marked in our dark memories.

A supporter of the ‘Baroda Group’, he was a strong advocate of the pedagogy, emphasizing on contemporary narrative and figurative arts. It led him to establish the Kasauli Art Centre in 1976 , a site of discourse, and he was actively involved in even recently creating infrastructure development and residency programmes before ill health took over. Vivan Sundaram had a long association with and was passionate about the Radical Painters and Sculptors Group. He created the famous Seven Young Sculptors exhibition with major artists from radical groups. He was always accessible to anyone who was interested in connecting with him and remained young at heart while encouraging younger artists to engage in discussions and create art in the Indian political art domain. He was a co-founder of the Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust (SAHMAT) and many younger generations of artists had the privilege to be invited and be part of all events of the trust, to learn to be politically active and respond through artworks.

Vivan has played a huge role in supporting the Kochi Biennale Foundation to navigate the hurdles in the implementation of its first edition. His support comes not only from his political alignment to the left but also from his devotion to familiarising people with art. He always wanted to create better forums for artists to come together and engage in dialogues. I am reminded of his pursuits to conduct a Biennale in Delhi in 2005 which did not however happen but he saw the fulfilment of that dream in Kochi. Vivans work Black Gold he produced as a site specific project was one of the first works 'made in kochi ' which changed the perceptions among people about art making .... His installation clubbed with videos along with a huge display of pottery shards loaned from KCHR was one of the memorable collaborations Biennale did with a research institution. The work still carries a deep memory as it symbolised excavations as metaphor at the first edition of the biennale. He was an artist and political activist who stood by and supported the foundation with moral and political backing, and financial help to build the much needed ecosystem for art which celebrates India's multiculturalism and diversity. With his untiring thirst to bring changes to India’s art world, he played a major role in the addition of the Students’ Biennale vertical to the Kochi Biennial. He was one of the greatest supporters of the Students Biennale and organizations he was associated with came on board to help the project move forward in building new momentum in the Indian art education system.

Vivan , a comrade from the core, was also in love with Nehruvian ideals and democratic processes. His deep association with Leftist ideology gave him many friends in the communist party. He had met and interacted with the likes of EMS Namboodiripad and had close associations with many left leaders of our time. At the same time, he maintained a certain political autonomy and independence as an artist and spoke truth to power, living in Delhi, a city that in India is a synonym for absolute power.

Now he has left us at one of the most crucial periods in the history of modern India, at a time when such ideals are under sharp attack from dark forces that are bent upon discrediting seekers of knowledge, demonizing the other, and crushing dissent. The biggest tribute that we can offer him, therefore, is to resist such efforts to weaponize hate through a medium that he has used all his life to resist similar forces who were up to no good.

We will miss him, but his memories embolden us to continue the struggle.