Directed by Cristina D. Silveira

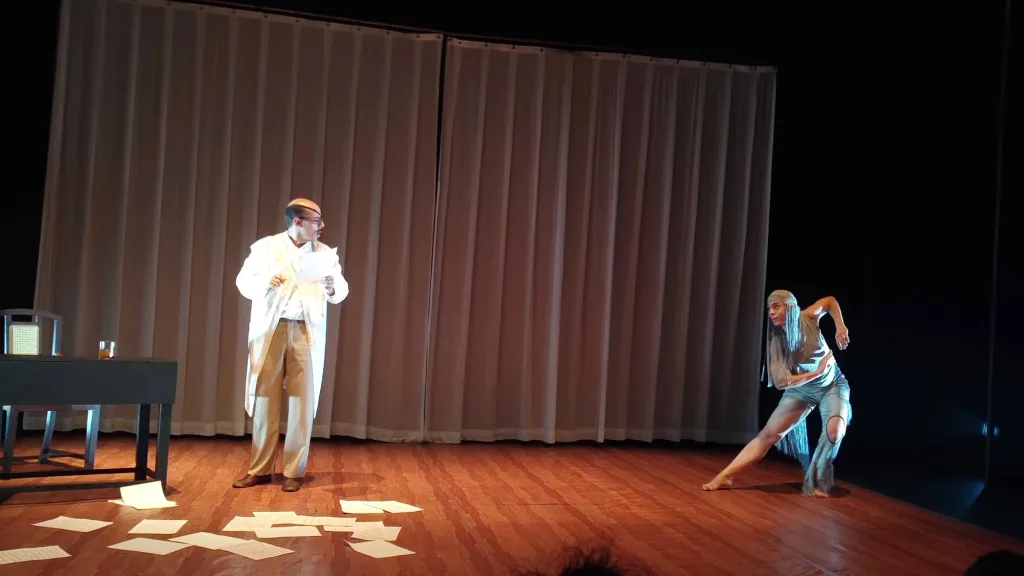

Cast : Carla González Pérez, Memé Tabares and Jorge Barrantes

Language: Spanish and English

Production: Karlik Danza Teatro, Spain

History is often a thicket of ink, grown dense by the towering legacies of men. In the shadow of "the James Joyce," his daughter, Lucía, was long relegated to a tragic footnote a "case study" for Jung, a "passé" for Beckett, or a "burden" for her family. But in Karlik Danza Teatro’s breathtaking production, the ink fades, and the flesh awakens. Lucía Joyce: A Small Drama in Motion is a poetic reclamation of a stolen life.

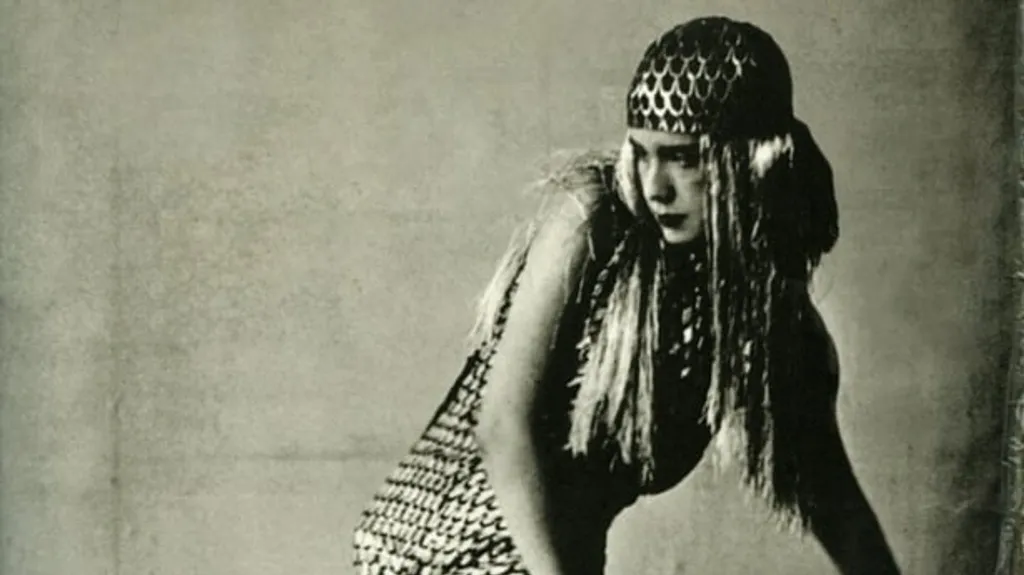

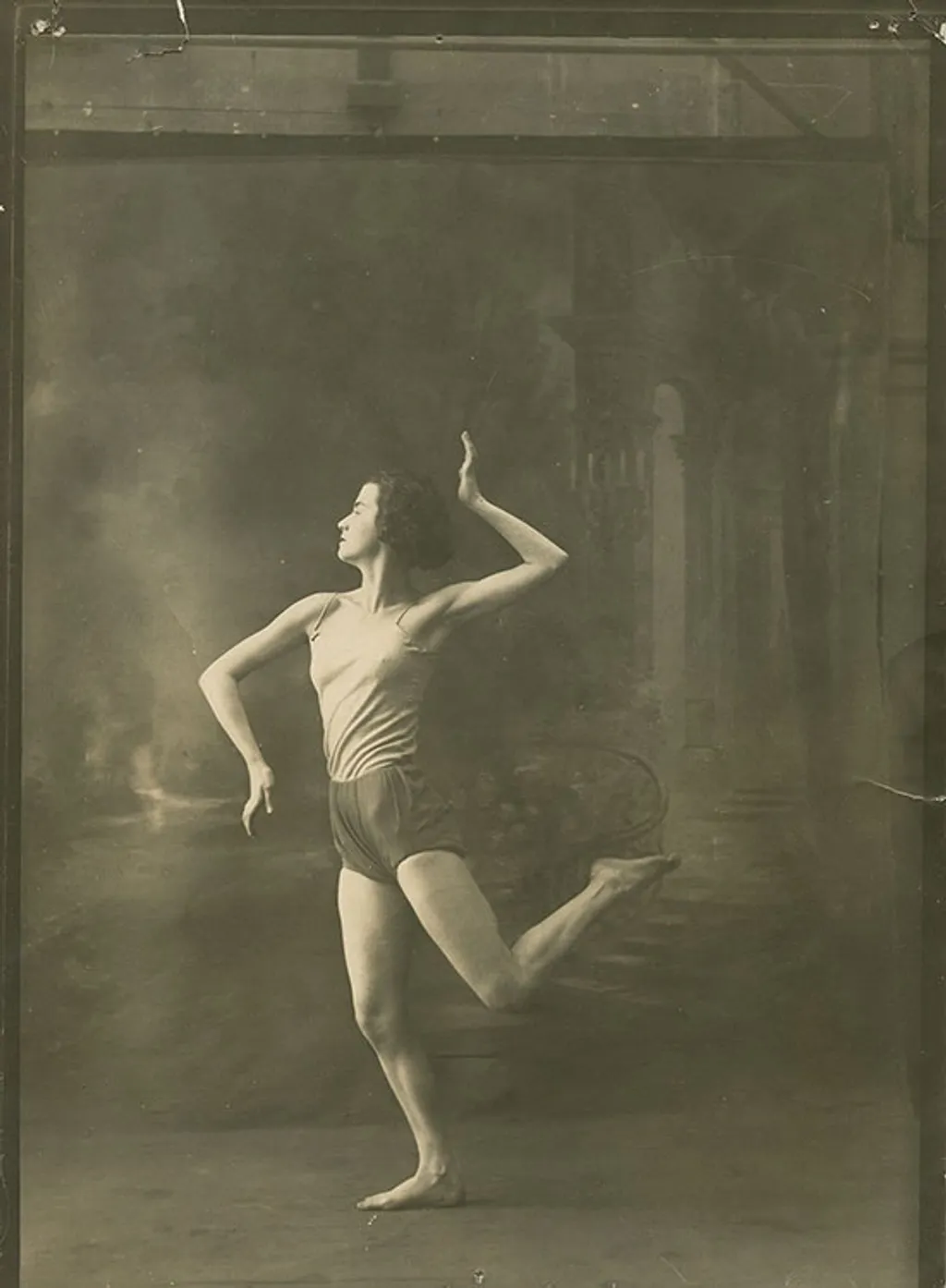

The production draws deeply from the haunting reality of Lucía’s early years, moving through the nomadic chaos of the Joyce household from Trieste to Zurich to Paris. While her father dived into the linguistic depths of his manuscripts, Lucíafound a different tongue. As the play illustrates through the ethereal performance of Carla González Pérez, Lucía was a pioneer of modern dance, a woman who believed in her teacher that "dance is not a technique but a spiritual moment." Under the tutelage of Raymond Duncan, she learned to move like water and wind. The production captures the "remarkable plastic talent" that once charmed Parisian critics, reminding us that before she was a patient, she was a professional artist. For Lucía, movement was the ultimate sanctuary; as she poignantly cries out in the play, "When I dance, everything that terrifies me vanishes."

Beyond its biographical roots, Dancing with Lucía serves as a beautiful, kinetic tribute to the pioneers of expressive movement. The choreography breathes with the spirit of Mary Wigman’s Ausdruckstanz, channelling that same raw, existential intensity. One can see the ghost of Pina Bausch in the play’s repetitive, emotive gestures and its ability to find the "art of feeling" in the mundane. Furthermore, the structural precision and the dialogue between the body and space feel like a nod to Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker. By echoing these matriarchs, the production places Lucía Joyce back where she belongs: in the lineage of women who revolutionised how the human soul speaks through the skin.

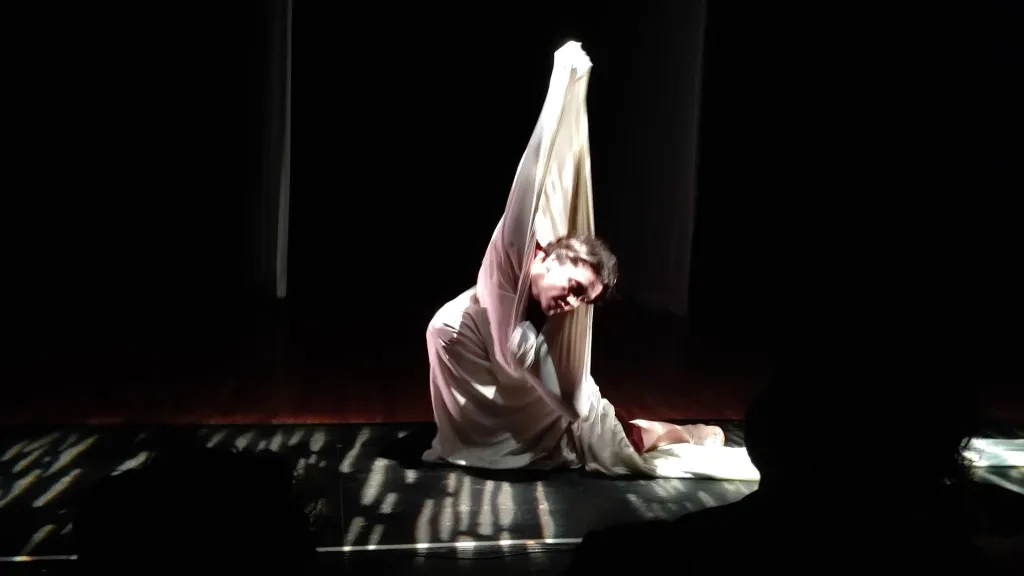

One of the most profound elements of this production is the symbolic use of the chair. In the Joyce household, and later in the sterile rooms of clinics and hospitals, the chair represents the domestic and clinical "sitting" expected of a woman of her time. The chair is the site of her suppression. It is where she is forced to sit while men discuss her "condition," where she is poked and prodded by doctors, and where she is expected to be a silent muse. Lucía’s frustration with this physical cage is palpable; the chair becomes a metaphor for the decades of confinement that sought to domesticate her wild, artistic spirit. When she finally rises from the chair for a long, powerful dance sequence, it is a visceral rejection of stasis. It is a heartbreaking realisation that while she was born to fly, the world insisted she remain seated. She laments, "My wings don’t spread from the body," suggesting that the very institutions tethering her ability to soar meant to "heal" her.

The directorial vision of Cristina D. Silveira uses multimedia to bridge the gap between a shattered present and a vibrant past. We see the elder Lucía (played with gravity by Memé Tabares) projected onto shifting white curtains. She prepares her final letter in 1982 from St. Andrew’s Hospital, looking back at the younger Lucía on stage. This interaction creates a haunting "wow" effect, as the 75-year-old woman gazes at the spirit she once was. The lighting design creates an intimate, almost spectral atmosphere, while the sheer curtains move dramatically, mimicking the "Bora winds".

Jorge Barrantes delivers a tour de force performance, inhabiting the men who defined and confined Lucía. With seamless precision, he portrays the complex spectrum of her life: the father (James Joyce), the brother (Giorgio), the psychoanalystCarl Jung, and a brilliant, brooding Samuel Beckett. The play pulls no punches regarding the collateral damage of James Joyce’s genius. Lucía’s accusation rings out with devastating clarity: "You sacrificed my vocation to protect yours."

The production also highlights the clinical gaze that failed her. We hear the chilling assessment of Jung: "Her being is petrified; her soul is dying prematurely." The treatments used in the play serve as a stark illustration of Michel Foucault’s critiques in Madness and Civilisation. We see the "medical gaze" in action where Lucía ceases to be a human being and becomes a specimen to be categorised, silenced, and disciplined. Foucault argued that the asylum was not a place of healing but a site of power where "reason" sought to exile "unreason." In this production, the doctors and their primitive treatments represent the Great Confinement, in which science is used as a tool of social control to extinguish the "fire in the brain" that James Joyce so famously described. Lucía’s own voice counters this psychiatric establishment with devastating simplicity: "Words strangle me, they don’t heal me," and "All treatments take me away from the soul."

Despite being the daughter of a linguist and polyglot, Lucía found that human connection eluded her in every tongue. In one of the play’s most biting lines, she remarks, "I’ve learnt 4 languages, and in none do men care about me." The play dives into the heartbreak of 1928 the moment Lucia’s world began to crack. Beckett, hungry for the "Master’s" approval, used the family to get close to James, inadvertently shattering Lucia’s heart in the process. She loved him, but he said to her, ‘You’re fire, and I’m dead’. This isolation leads her to a dark, internal landscape, prompting the echoing question from the Divine Comedy, which Beckett gifted to her: "Do you know what it is to live like in a hell?"

The closing sequence features a literal chord connecting father and daughter, a physical manifestation of their intense, consuming bond. It visualises Jung’s famous observation: while James Joyce was diving into the subconscious river, Lucía was drowning in those same waters. As they pull and push against one another, we see the weight of a father’s love that was both a shield and a shroud.

Lucía Joyce is a masterpiece of "the art of feeling." It is a beautiful, harrowing production that restores the body of a woman history tried to turn into a ghost. It reminds us that LucíaJoyce was not a footnote to her father's fame, but a woman who sought to create beauty in a world that insisted she remain silent and seated. The tragedy of Lucia Joyce is compounded by the erasure that followed her death. The play’s epilogue reminds us of the final cruelty: the destruction of her novel, poetry, and letters by her nephew, Stephen, in 1988.

However, Karlik Danza Teatro refuses to let her remain a "supine space." At the end, through lines like "Now the wind doesn’t strangle me, it cradles me", the production gives Lucia back her agency. It challenges the misogyny of the 1930s and perhaps our own time where the word "artist" so rarely existed in the singular feminine within the Joyce household.