To step into the world of Vaikom Muhammad Basheer is to enter a space where the boundaries between the mundane and the miraculous are porous. In Rajiv Krishnan's directorial venture, Under the Mangosteen Tree (UTMT), the Chennai-based theatre group Perch does more than adapt the "Beypore Sultan's" work; they exhume his spirit. This production, an adventurous mix of seven main stories by the great Malayalam writer, is a lush, non-linear odyssey that stitches together the author's disparate tales into a single, breathing entity, held together by the connective thread of Basheer's own life. Selected for the National Category of Plays at the International Theatre Festival of Kerala (ITFOK) and staged at the KT Mohammed Theatre, the play serves as a heady concoction of love, humour, and pathos.

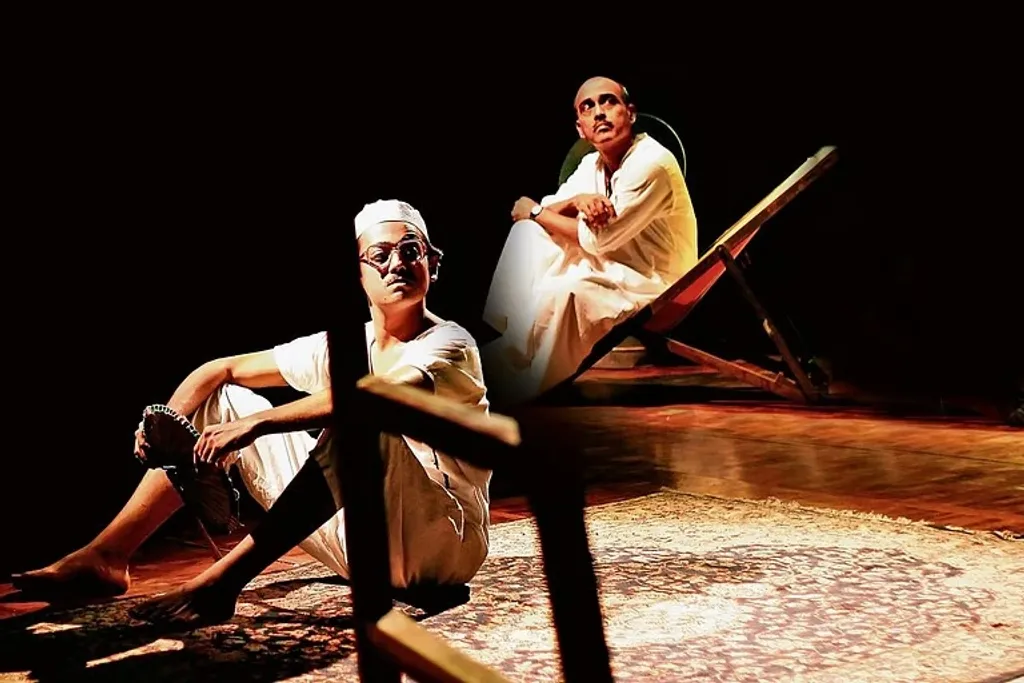

At the heart of this "heady concoction" is Basheer himself, who plays narrator, participant, and witness in turn. Portrayed by Paul Mathew, the play utilises a clever framing device to unify its variety of themes. The narrative begins as Basheer moves into a new house, one rumoured to be haunted by the ghost of a young girl who committed suicide there a character he lovingly calls "Bhargavi Kutty." The ghost's unseen but tangible presence serves as the initial anchor for the storytelling. In a bargain struck between the living and the dead, Basheer offers the spirit a story in exchange for her silence, asking her why she would take her life for love. This meta-theatrical layer a story within a memory within a play captures the quintessential "Basheerian" essence: the idea that life is an endless series of anecdotes, some tragic, some absurd, but all deeply human.

The writer is everywhere in this production. He is steeped in the words he has penned; he comes alive in the actors who bring his stories to life, and he is at home in the rustic setting that recreates his world. As Basheer speaks to the invisible spirit, the stage dissolves into the past, and the persona of the "Sultan of Beypore" begins to unfold. This persona is a masterful blend of historical reality and self-fashioned myth. The play navigates the delicate line between Basheer the man a fierce political revolutionary and Basheer the legend the eccentric philosopher sitting under the mangosteen tree.

In reality, Basheer was an anti-colonial activist and journalist who was arrested in 1943 for "seditious" writing against the British Crown. The play captures this biographical anchor but pivots toward a legendary persona by focusing on the humanity found within the struggle. While history records the hardship and torture endured within the grim walls of Kannur Central Jail, the play's adaptation transforms the prison into a stage for a surreal romance. We see a younger Basheer finding a lifeline in the disembodied, flirtatious, and cheeky voice of a woman prisoner on the other side of the high prison wall. Their conversation runs the gamut from anticipation to love and pathos, emphasising the author's belief that the human spirit and its capacity for love remain unconquerable even in the most oppressive political environments.

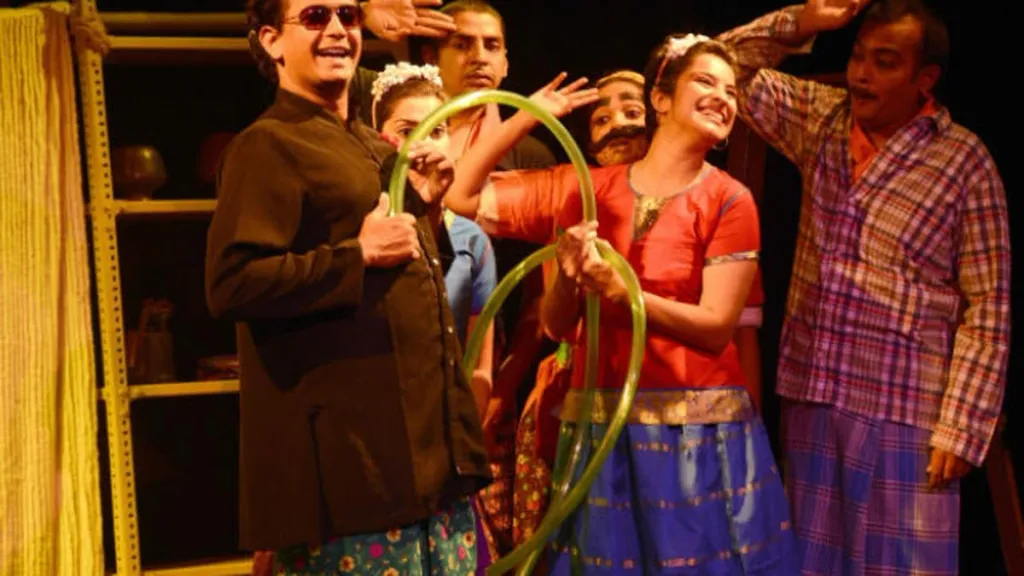

The production refuses to be pinned down, oscillating wildly and successfully between slapstick and profound existential dread. This variety of themes is presented one within the other, ensuring that even with a non-linear plot line, the scenes transition effortlessly and the story flows smoothly. The domestic problems of Jameela (Darshana Rajendran) and Abdul Khader (Dayal), for instance, are replete with slapstick humour that elicits genuine laughter, grounding the play in the earthy reality of Kerala's social fabric. Darshana Rajendran

Yet, the play is equally comfortable exploring the anguish and disillusionment of the soldier (Vinod Ravindran) who has returned from war, unable to assuage his guilt of having killed his friend. Interestingly, while the soldier scene dealing with the weight of this guilt did not translate as effectively on stage as it could have, it was ultimately rescued by a moment of pure auditory beauty. The goat girl (Maya S. Krishnan), who sings at the conclusion of that segment, saves the scene with the sheer power of her voice and words, providing the emotional punctuation the dialogue struggled to reach.

This particular arc regarding the soldier's guilt is a national confession, critiquing the state's use of ordinary people as fodder for patriotic violence, and is further elevated by the earnest performance of Anand Sami as the soldier's transgender lover. Sami's portrayal speaks of loneliness and longing, winning not just the soldier's acceptance but also that of the audience. By introducing a subversive identity that finds acceptance in the wake of war's destruction, the play challenges the rigid, patriarchal definitions of a "national hero," suggesting that the actual political act is not killing for one's country, but finding empathy in the margins of society.

Woven between these stories are many more tales of loss and longing. As the young writer narrates to his prison love, another story unfolds: the unlikely love story of Saramma and Keshava Nair. As two people from different religious backgrounds, their quaint conversation about marriage offers a realistic portrayal of life, showcasing Basheer's unique voice and his focus on everyday life in Kerala. The lines, infused with Malayalam words, bring out the charm of the language and add a touch of local flavour, reinforcing the "Indian-ness" of the experience.

To put seven stories into a single play is undeniably ambitious. Because of this density, the concoction might not be as consistently effective as it could have been had the focus remained on four or five stories. While it is admittedly difficult for a creator to decide what not to select, it is a vital part of the process to determine which stories are most relevant to be communicated to the audience in a single sitting.

Reducing the play's count to four or five stories would likely have trimmed the performance by about 20 minutes, making the overall experience much more effective. The play required a director with a sharp eye to identify what could be cut without losing the work's soul; such an edit would have further helped the production reach its full potential.

Despite the length, the intellectual depth remains sharpened by segments like The World-Renowned Nose(ViswavikhyathamayaMookku). The story begins with a simple labourer whose nose grows to reach his navel, and his subsequent rise from dire anonymity to unparalleled fame. This physical absurdity serves as a sharp critique of post-independence Indian society and the global obsession with celebrity and dogma.

Through the story of the nose, Basheer mirrors the rise of political demagogues. The man with the long nose has no intellect or talent, yet the masses flock to him, highlighting how political systems often prioritise symbolism over substance. As the nose becomes famous, various factions socialists, capitalists, and religious groups claim the man as their own. The play depicts the chaotic rise of "the long-nose party," a direct jab at the mindless factionalism of his era and a satire on how political parties co-opt every possible phenomenon to serve an agenda. Long before the era of "fake news," Basheer predicted the media's power to create truth out of thin air; the play captures how journalists turn a medical anomaly into a divine miracle, reflecting Basheer's scepticism toward the propaganda machines of the Cold War era.

The title "Sultan of Beypore" was originally a tongue-in-cheek moniker for a man who lived a life of extreme simplicity, and the play reflects this through its minimalist staging. Historically, after years of wandering as a Sufi, a cook, and a sailor, Basheer settled in a humble home in Beypore. The play's adaptation, utilising ropes, rods, and ladders to signify his world, mirrors Basheer's own ability to find wealth in the "nothingness" or Shunyata. He isn't a Sultan of gold, but a Sultan of stories.

READ: HIDEAWAY'S ABYSS: MORALITY'S DIGITAL ECLIPSE

The set design eschews literalism, relying instead on the audience's imagination to breathe life into the space. A collection of rustic pots and props, a few strategically placed step ladders, and a solitary grandfather chair beneath a mangosteen tree ingeniously fashioned from a skeletal frame of rods and ropes are all that is required to manifest the environments for seven distinct narratives.

Accentuating this spatial economy is the choice of old-world Malayalam, Tamil and Hindustani music, which anchors the atmosphere in a bygone, lyrical era. These old-school melodies do more than provide a backdrop; they function as a profound medium for transitions, smoothing the shifts between stories and emotional registers. Within this frame, the ensemble cast exhibits remarkable versatility, slipping into a multitude of roles to deliver a performance that is equally rife with slapstick humour and piercing emotion. Ultimately, what resonates deeply is the sheer sincerity of the entire affair.

The play's use of language acts as a bridge. Historically, Basheer broke the "high-brow" Sanskritized tradition of Malayalam literature by using the colloquial, everyday language of ordinary people. The play honours this by maintaining a rustic, unpretentious tone that makes the audience feel like they are sitting on the ground with him, rather than watching a distant historical figure. The "Writer/Sultan" we see on stage is less a chronicle than an eternal spirit a man who used humour to shield himself from the tragedies of war, prison, and loss.

The interaction between the young Basheer and the female prisoner across the wall remains one of the most subtle political satires in the play. "Even the air between these walls belongs to the Emperor, yet our voices belong to us." This dialogue underscores the central theme of Basheer's life: Individual Sovereignty. By falling in love through a wall, the characters render the prison a symbol of state control completely irrelevant. It is a quiet, poetic rebellion against the carceral state, suggesting that human connection is the ultimate form of sedition.

In summary, Under the Mangosteen Tree is a dual-purpose triumph. It serves as an excellent introduction to Basheer for an audience unfamiliar with his work, while also serving as a moving tribute to those who already love his writing and wish to see their favourite author honoured on stage.

Basheer's genius, as captured in Under the Mangosteen Tree, lies in his ability to make you laugh at the very things that should make you weep. He portrays a world where the only sane response to a mad political climate is to tell a story so absurd that the truth finally becomes visible. The stories in this play Poovan Banana (Poovan Pazham), The Blue Light (Neela Velicham), Walls (Mathilukal), Voices (Shabdangal), The World Renowned Nose (Viswavikhayatamaya Mookku), and The Man(Oru Manushyan) all share a common vein of deep empathy.

Following the Kannur jail story, the lead actor delivers a short concluding monologue. While Paul Mathew's delivery remains earnest, this final speech feels redundant; everything the monologue seeks to convey has already been articulated through the sweat, laughter, and tears of the preceding scenes. The play finds its true, organic ending in the silence and togetherness of that final tableau, where freedom fighters, ghosts, labourers, and lovers all find their place in the shade of the mangosteen tree. To achieve a punchier, more effective resolution, this monologue could be easily skipped.

Darshana Rajendran, Maya S Krishnan, and Dharaneedharan are particularly outstanding. A standout moment of sharp, observational comedy is the scene between the two secretaries, played by Karuna and Aparna Gopinath; their chemistry creates a memorable vignette that lingers long after the scene transitions.

Furthermore, the encounter between the soldier (Vinod Ravindran) and his lover (Dharaneedharan) is portrayed with immense sensitivity. It stands as a powerful, subversive narrative a story of longing and acceptance that feels profoundly humanwithin the context of Basheer's universe.

As Basheer says, "In this all too brief phase of existence when life is bubbling with youth and the heart is fragrant with love..." it is essential to witness such theatre. Despite the need for a tighter directorial edit, it remains a theatrical achievement that is both intellectually stimulating and deeply entertaining. It honours Basheer's legacy by recreating the atmosphere of his mind—a place where freedom fighters, ghosts, and lovers all sit together under the shade of a tree, sharing the bittersweet fruit of existence.

▮

Directed by Rajiv Krishnan

Cast: Dayal, Darshana Rajendran, Aparna Gopinath, Maya S Krishnan, Paul Mathew, Karuna, Dharaneedharan, Vinod Ravindran